Meet 8 of the last home goods makers in America – Half of the shoes in the country were manufactured in the United States forty-one years ago, when Sara Irvani’s grandpa started a shoe business in Buford, Georgia. Even now, that number has dropped to 1%. “Shoe manufacturing had actually been in Buford from the late 1890s through the 1970s or so,” Irvani said. The Oka Brands facility is now completely isolated.

The contentious tariff campaign of President Trump has sparked discussions, debates, hopes, and fears over the future of American industry. Trump claims that he is increasing import taxes in an effort to encourage Americans to buy American goods and revive the manufacturing sector. An idea as old as the United States itself is the “Buy American” movement. At this time, however, the Buy American movement is encountering significant obstacles. Over the past five years, prices have been driven up by inflation, which has made inexpensive imports seem even more attractive.

Most Americans say they prefer American-made items, when they can find them, according to an October study by Morning Consult for the Alliance for American Manufacturing. However, it is possible that they are not trolling: Gallup survey reveals just approximately 40% of Americans consistently know where their toasters and T-shirts are made.

American manufacturers want attitudes to change

“Made in America means communities and jobs and supporting neighbors,” said Amity Messett, sales and marketing director at Liberty Tabletop, a firm that advertises itself as the last American manufacturer of stainless-steel cutlery.

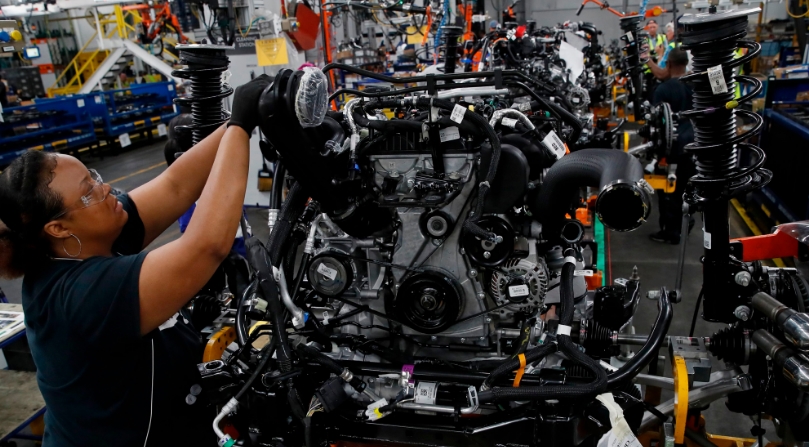

Manufacturing jobs plunge

The number of U.S. manufacturing workers has decreased from a record of 19.6 million in 1979 to 12.7 million in September 2025. As a share of all nonfarm jobs, manufacturing has declined from 29% in 1960 to 8% now. It hasn’t all been downward. A modest rebound has lifted the industrial employment from a low of approximately 11.4 million in 2010 to current levels, supported by a revived Buy American spirit.

“There is a very passionate but small consumer base that will buy American,” said Scott Paul, head of the Alliance for American Manufacturing. “And the reason that it’s passionate and small is that it’s hard to do.” The demise of American industry has played out over decades. No one president, political party, or foreign force bears all of the blame.

America accepted imports with the North American Free Trade Agreement, a 1994 deal that lowered trade barriers between the United States and its neighbors, Canada and Mexico. The formation of the World Trade Organization, or WTO, in 1995 began an era of globalization. China’s entrance to the WTO in 2001 swamped America with low-cost goods.

Some American companies transferred factories and jobs overseas, exploiting lower wages, cheaper materials, lax labor laws and insufficient environmental restrictions. Others closed, forced out of business by imported products that sometimes sold for less than it cost to create them. At some key time, each of the eight manufacturers covered in this research chose to remain in business, to maintain their factories in America and to compete against an increasing wave of imports.

Today, most of them don’t even bother to compete on pricing.

“I just don’t talk about price, ever, because there’s no point,” said Matt Bigelow, CEO of USA Brands, a manufacturer of flannel shirts, blue jeans and teddy bears. “Something like 90% or 95% of all the world’s toys and teddy bears and plush are made in China,” he remarked. If you go on Amazon and you hunt for a cheap teddy bear, you’re not going to find us.” Meet 8 of the last home goods makers in America

Instead, they compete on quality. Nordic Ware baking sheets, pressed at a plant in Minnesota, have been Wirecutter’s pick as best in class for more than 10 years. American Giant, based in San Francisco, sells a sweatshirt that Slate Magazine has named “the Greatest Hoodie Ever Made.” A journalist at CNET tested a pair of Oka Recovery slides and said, “My Feet Can’t Stop Thanking Me.” “Today, when we talk about ‘Made in America,’ we talk about things being done right and being accountable for what you do,” said Gat Caperton, owner of Gat Creek, one of a diminishing number of American furniture producers.

Quality, pricing and patriotism

That’s not to say American manufacturers never compete on pricing. American Giant offers Walmart with a made-in-America, all-cotton T-shirt that retails for $12.98. “That’s a testament to what can happen when you partner with a brand like Walmart that can commit to volume over a long period of time,” said Bayard Winthrop, founder of American Giant.

American Giant’s Walmart T-shirts often display some form of “Made in America” or “American Made,” sometimes flanked by an American flag. Patriotism suffuses the Made in America movement. The call to “Buy American” is as old as the Boston Tea Party, a forerunner to the Revolutionary War. A Depression-era Congress established the Buy American Act of 1933, encouraging American-made products in government procurement. Older Americans will recall Lee Iacocca’s bold automobile commercials of the 1980s, when American automakers struck back against imports.

Today, the movement’s most famous insignia is the created in USA mark, controlled by the Federal Trade Commission, which demands for a product to be “all or virtually all” created in the United States. American manufacturers want customers to know that their purchase supports jobs: Not just in their own factories, but in the factories that supply the stainless steel in Liberty Tabletop’s flatware or the cotton in American Blossom Linens, a brand that started as a retail store in Philadelphia.

“By buying one of our shoes,” said Irvani of Oka Brands, “you’re helping to shape the American economy and the structure of our society. Manufacturing employment ‒ I think it’s crucial to have them in our society.” Lately, though, the Made-in-America movement has been enmeshed in politics.

Trump’s tariffs and the Buy American campaign have been wrapped up in a bigger dispute over the polarizing policies of a divisive president. Chinese memes criticize his crusade to reindustrialize America. Democrats widely deride tariffs, yet the party used to embrace them. Much of the public dislikes import taxes, which many Americans, and most economists, link with rising prices.

A huge American flag on a website might appeal with Republican Trump fans, who are more likely to support his tariffs and to hang a flag outside their homes, according to a recent YouGov/Economist poll. A subtler American-made message would appeal to Democrats, who have more ambivalent sentiments about tariffs and the flag itself.

Naturally, American producers strive to reach both sides.

“This is like buying local, in effect, but buying local all over our nation,” said Todd Lipscomb, proprietor of the site MadeInUSAForever, a retail showcase for American manufacture. “This is not a Red State or a Blue State issue,” Lipscomb added. “This is red, white and blue.”

In any event, manufacturers have learnt that “Made in America,” however resonant, is not enough to reach American consumers. “Patriotism and saving jobs doesn’t get you that far,” said Caperton of Gat Creek. Meet 8 of the last home goods makers in America

Standing apart from the competition

Bigelow, of USA Brands, says American-made products “have got to have at least two or three ‘uniques,’” attributes that set them apart from imports. American provenance counts as only one.

For Bigelow’s Vermont Flannel brand, the Green Mountain State address is a marketing advantage. Another is the quality of his company’s flannel, which consistently gets plaudits on “Best Flannel” lists.

Many of America’s remaining household goods businesses trade on colorful origin stories, which generally feature immigrants, shoestring operations and the pursuit for the American ideal. Dave and Dorothy Dalquist launched Nordic Ware in 1946 in Minneapolis. She knew Scandinavian food. He knew metallurgy. They began manufacturing cooking things “that are tough to pronounce if you’re not Scandinavian,” said Jennifer Dalquist, their granddaughter and executive vice president of Nordic Ware. Meet 8 of the last home goods makers in America

The Dalquists designed the Bundt pan, which caught off in the 1960s after a Bundt cake won a prize in the high-stakes Pillsbury Bake-Off. Oka Brands took shape when the Irvani family fled Iran after the 1979 revolution, which cost them their shoe business. They founded a new enterprise in rural Georgia. As other American businesses went bankrupt and the competition moved overseas, both the Dalquists and the Irvanis resisted pressure to shift their factories elsewhere.

“My father and grandfather were being told by so many people in the industry, ‘You’ve got to move overseas, or you’re going to go out of business,’” Dalquist said. “Environmental laws and human rights law over there are just nonexistent,” she remarked. “So that didn’t sit right with our family.”

The remaining American manufacturers find a painful irony in the trajectory of American policy. On the one hand, federal regulators enforced a minimum wage, child labor regulations and severe standards for occupational safety and health in American enterprises. At the same time, relaxing trade laws were “allowing our biggest corporations to ignore all of them and go make things overseas,” said Winthrop of American Giant.

Images of child laborers and sweatshops probably compel some shoppers to buy American. U.S. firms can also represent their products as dependably safe: When every component originates from an American manufacturing, the manufacturer can vouch for its contents. “You’ve got full knowledge and transparency about what goes into it, and how people are treated,” said Irvani of Oka Brands. Meet 8 of the last home goods makers in America